I recently started reading Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino's 2018 collection of essays on self-delusion. "The I in the Internet" explores the five intersecting problems of being online:

First, how the Internet is built to distend our sense of identity; second, how it encourages us to overvalue our opinions; third, how it maximizes our sense of opposition; fourth, how it cheapens our understanding of solidarity; and, finally, how it destroys our sense of scale.

I cannot summarize this essay for you – Tolentino's writing is the ultimate form, and it's on sale. (If you're busy or cheap, you can listen to Tolentino discuss the Internet with Ezra Klein on my single favorite episode of Vox Conversations, formerly The Ezra Klein Show.)

The practice of personal newsletter publishing is troubling given the Internet's way of “collapsing my identity, opinion, and action” into one, which is something that I was aware of but couldn't articulate before Trick Mirror. I'm conscious that, in every newsletter, I am communicating some identity, and I must sell you this performance in exchange for your attention, your time, your reply, or whatever my goal is. Newsletter writing is mostly words, but it's still a performance, which is no more dignified than it is on my Instagram or my Twitter.

When I created my Substack account in August, I imagined having a lot of things to say during my gap year – probably reflections on work, people, or pandemic living. I went ahead and entered all my details, picked a clever name, and made my cover art by arranging some magnets on the fridge. My goal was to sharpen my voice and find a way to exist more authentically than I could on other platforms.

I fantasized about reaching through the opaque fabric of the Web, finding friendship, and establishing more of my digital identity with each letter. If all I got out of this adventure was some writing experience and a few interesting replies in my inbox, I'd be happy.

And then I didn't write for a few reasons:

I worried about taking up undue space. I had forgotten the crucial precondition that "space" is one of the Internet's unlimited resources and that people who don't want to hear from you can scroll and click away from you as quickly as you appear.

The prospect of further self-performance had exhausted me before I could begin. The subject of me and my thoughts felt tedious, trivial, and unrewarding. A personal newsletter seemed at best, silly or vain, and at worst, selfish, as new events reified the permanent disaster of this world in new ways each day.

Many newsletters are useful or helpful, and I felt pressure to follow. But I didn't want to be useful; I wanted to talk to people. Plus, usefulness easily gives way to the suffocating wellness gospel that permeates the Internet—the endless stream of taut reminders to stop scrolling and take a deep breath or reframe the problem and do some stretches or shove my phone in a drawer. Imperatives are everywhere, crowding your inbox and your Slack. I didn't want to join the chorus of people telling you what to do.

Simultaneously fed and confined by this Internet umbilical cord, I refused to add my newsletter to the list of things to engage with on the Internet. To feel worthy of space in your inbox, I needed to be certain that I was a uniquely strong and interesting writer, the thoughtful author of an email you'd actually look forward to. I wanted to be worth the real estate in your brain, worth your time, worth the open rate. Clearly, I'd forgotten that I needed to write for my writing to gain any worth. So I thought about writing a lot and didn’t write anything at all. Months went by, my Substack collecting cobwebs in the back room of my Internet brain.

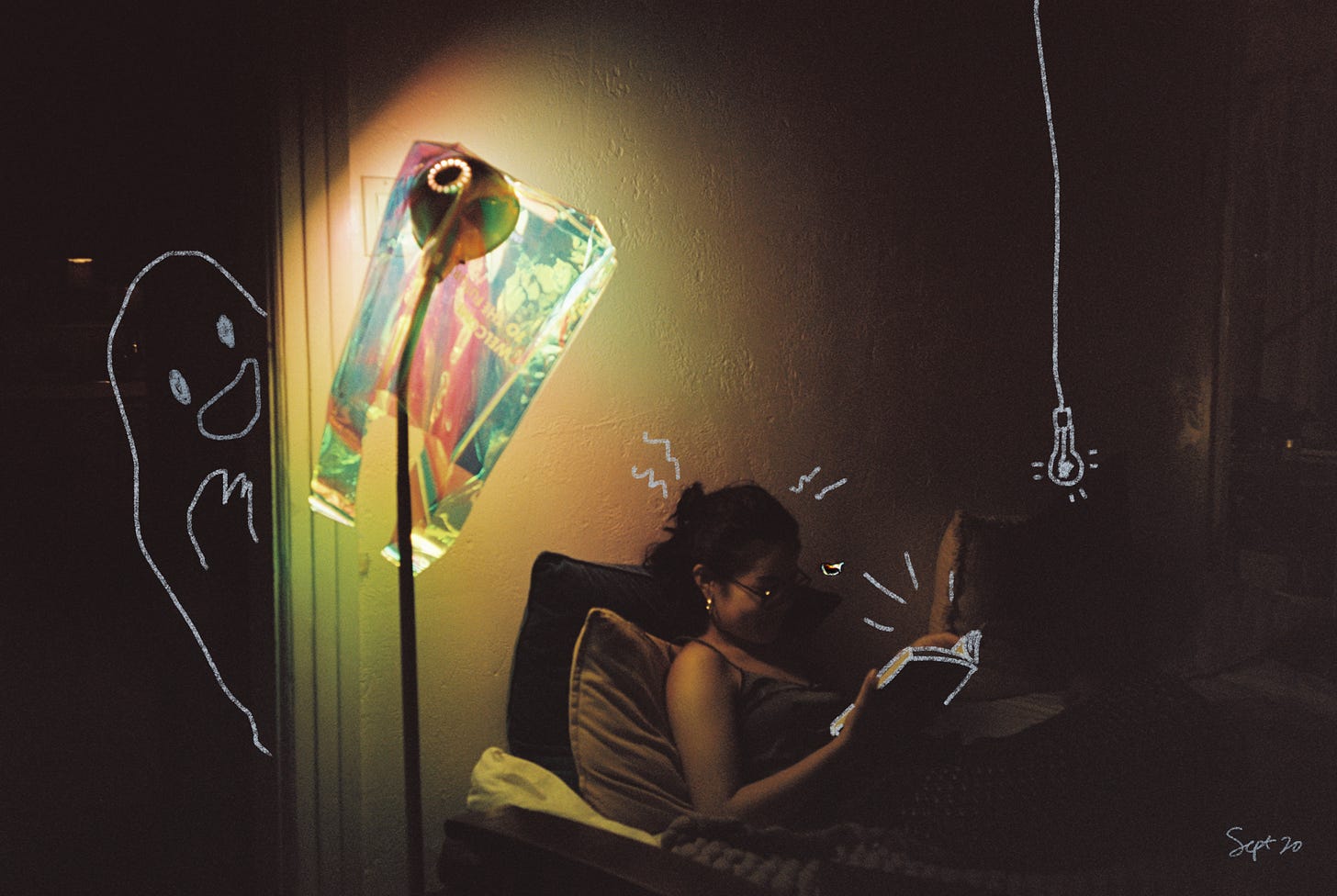

Though I'm ready to write now, it was probably for the better that I kept from writing in the fall and winter. Writing about myself made me feel heavy. Instead, I thought about others. I read collections of letters, cooked for the house, and texted my grandfather. When I felt like expressing myself, I avoided words by painting self-portraits:

In my notebook, I wrote the following:

I feel lighter when I am not the gravitational center of my own universe.

This is not a noble sentiment, but one of self-preservation. I wish to exist at a distance from what Tolentino calls, "this feverish, electric, unlivable hell" (the Internet), and committing to a newsletter means committing to self-performance.

But separating myself from my Internet profiles in lockdown is like forfeiting existence, or some otherwise fatal rupture. Is this sad? Probably, but choosing to stay online is also a matter of self-preservation.

We, the citizens of the internet, are willful participants in this paradox. We've agreed to commodify ourselves — distributing versions of ourselves across a series of posts and subscribing to one another, sometimes through a paywall. It's strange. But like Tolentino, I am "chained to" myself online, which has "made me self-conscious." And like Tolentino, I am still here, writing. So, if you've gotten this far, thank you for reading.

My writing is not typically meta-analytical, and I hope it won't continue to be — both for your sake and mine. I prefer kids' books, anyway, so this is a key change for me, and I plan to spend the next letter writing about the books I read that are explicitly meant for children. Maybe after that, I'll write about the cooking I've been doing. But I wanted to share how my thoughts are affecting the way I write and relate to this newsletter.

I mentioned earlier that I'm writing this to talk to people. That's really why I'm here. I'd love to hear from you, even if we don't know each other. What identities are you performing these days, and to whom? You can reply to this email!

(Read Trick Mirror!)

Beez

This is precisely the same conundrum I find myself in, although I haven't been able to articulate as wonderfully as you just did. The idea of being a part of a generation that unwittingly committed to commodifying ourselves, digitally, in an act of self preservation. Looking forward to hearing more and thank you for your writing!

I love this! Don’t feel bad about taking up space and wanting to express yourself or build your identity through the internet. Our virtual identity is kind of just as important as our “in-person” identity now and it’s intertwined. We can use our social media or virtual channels to explore ourselves, express and get to know ourselves in ways we couldn’t before. So think of it as a positive thing, and as another way we can connect and bond with other humans too.